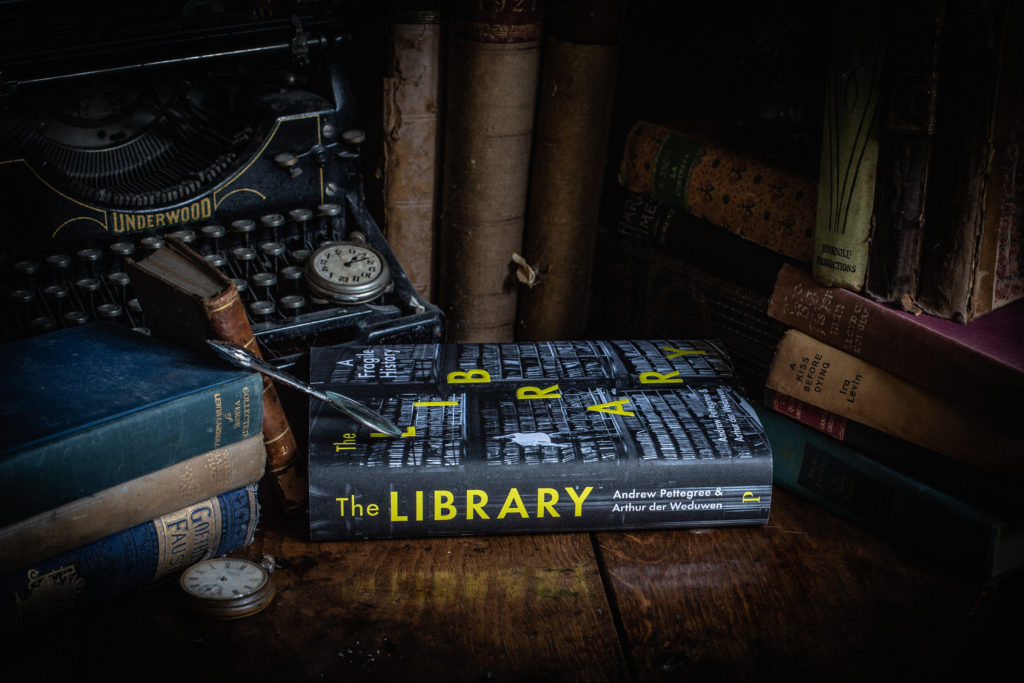

The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen

Throughout their long and tumultuous history libraries have taken almost every form imaginable, from humble wooden chests to vast palaces of marble and gilt. But one thing has always remained the same: the immense, sometimes obsessive lengths to which humans will go in order to acquire and possess knowledge.

In this, the first major work of its kind, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen explore the rich and dramatic history of the library, from the famous collections of the ancient world to the embattled public resources we cherish today. Along the way, they introduce us to the antiquarians, philanthropists and eccentrics who shaped the world’s great collections, trace the rise and fall of technologies, ideologies and tastes – and reveal the high crimes and misdemeanours committed in the pursuit of rare and valuable manuscripts.

From the age of the scroll to the disappearance of the bookmobile, the story of a library is also the story of the society or individual that created it: this erudite and fascinating account reveals what libraries can tell us about ourselves, and why we continue to collect, to destroy – and to make the library anew.

Thank you very much to Andrew, Arthur and all at Profile Books for sharing the following extract from The Library: A Fragile History with CILIPS.

According to the international Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, in 2020 there were still more than 2.6 million institutional libraries worldwide, including 404,487 public libraries. Almost all of them still have books. New libraries are still built. The example of France quoted in the last chapter is quite unique in Europe, but Europe has its fair share of spectacular new libraries: the national library of Copenhagen (the Black Diamond), an inspiration for the new Latvian national library in Riga. The destroyed Norwich library has been replaced by a new community hub, while Manchester has recently completed a sensitive regeneration of the central library, one of the oldest public libraries in England. The renovated library is now replete with the appropriate levels of convivial meeting space, and with a whole wing allowing patrons to combine a trip to the library with the opportunity to see council officers about housing and passport issues. New York recovered from the abandonment of the Foster redesign for the New York Public Library with a spectacular new branch library on 53rd street.

Technology moves with lightning speed. The distance in time between the beginning and domestication of innovation shortens exponentially with each era. but the death of the book, predicted with great confidence with each new communication invention, just refuses to happen. In 1979, the head of the RAND corporation announced that libraries would soon be obsolete. A good-natured wall chart of technological extinction predicted 2019 as the year the last library would close its doors. Yet these tattered, battered heritage technologies refuse to expire, and sometimes, for those who have attempted to get ahead of technology, the future turns out to be very temporary: witness the rise, and discreet departure, of the CD-ROM, very much yesterday’s future of books. The e-reader, Amazon’s Kindle, seems likely to follow. At least one futurologist is beginning to have second thoughts about libraries. ‘I thought they’d go virtual and that librarians would be replaced with algorithms. Apparently not.’ Why have they survived? ‘Libraries are slow-thinking spaces away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life.’

The book too lives on, for precisely the reason Jeff Bezos, looking for the right product, fixed upon books at the core of Amazon. Books do not spoil, they are easily transported, they come in relatively uniform sizes, and customers have a good idea of what they want. You could add, perhaps of less benefit to a tech entrepreneur looking for repeat sales, they are sturdy and resilient, they do not require servicing or replacement parts, and they provide cultural capital: either to be admired as an adornment of the home or office, or to be shared, loaned or cherished …

It is hard not to think that the health of the library will remain connected to the health of the book. The book, the artefact, has proved exceptionally resilient through the centuries: surviving the collapse of the Roman Empire, the media change from manuscript to print, the Reformation and the Enlightenment, carpet bombing and numerous attempts to limit access to unacceptable texts. Most recently it has seen so many of the technological pall-bearers sent to conduct it to the crematorium: microfilm, the CD-ROM, and now the e-reader. The sheer tangibility of the book is a key element of its success, and its versatility: as manual, totem, encyclopaedia and source of entertainment. And the library, as location and concept, has shared this mutability.

The Library: A Fragile History is out now in hardback, published by Profile Books.

About the authors:

Andrew Pettegree is professor of Modern History at the University of St Andrews and one of the leading experts on Europe during the Reformation. He is the author of the prize- winning The Book in the Renaissance and The Invention of News, among other publications. He is a former vice-president of the Royal Historical Society and the founding director of the Universal Short Title Catalogue.

Arthur der Weduwen is a British Academy postdoctoral fellow and deputy director of the Universal Short Title Catalogue at St Andrews. He is the author of several books on the history of newspapers, advertising and publishing. He owns a small library of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century books, which, as the research for The Library has shown, is probably doomed to be dispersed.

Praise for The Library:

‘Outstanding … a history of libraries from the ancient world to yesterday, it is fetchingly produced and scrupulously researched – a perfect gift for bibliophiles everywhere’ John Carey, Sunday Times

‘Excellent … rigorous but riveting history’ Dennis Duncan, Spectator

‘A sweeping, absorbing history, deeply researched, of that extraordinary and enduring phenomenon: the library’ Richard Ovenden, author, Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack

‘What is a ‘library’? Is it a mute display of personal wealth and power, or of a humble devotion to God? A routine community resource, or a waste of taxpayers’ money? In The Library, we are led nimbly through the centuries, seeing how it has been all of these things and more, as the authors place on the shelf a cornucopia of bookish history.’ Judith Flanders, author, A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order