New Voices RGU Student Series – Helen Blackwell

Category: New Voices, New Voices, RGU Student Series

In the Robert Gordon University Student Series blog, we share the views of RGU students from the MSc in Information and Library Studies course.

Today, we hear from Helen Blackwell, who is currently studying on the MSc Information and Library Studies course at RGU. In her blog, she shares her take on the critical importance of digital literacy in schools both during and after the pandemic, and what skills school librarians can prioritise to be the best possible support for students and their families.

Digital Literacy in the Post Covid-19 School

In December 2019, COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2: a new form of coronavirus) was first documented in a human case. Almost one year on, the world is quite a different place. At the time of writing (29th November 2020), globally there have been 61.6 million cases, and over 1.4 million deaths (WHO Coronavirus Disease Dashboard, 2020). The digital era has allowed countries to share information and work together towards keeping life as normal, and as safe, as possible, in a way that has been unprecedented in previous pandemics. Digital literacy is now, more than ever, important as we strive towards a new post COVID-19 world.

Working in schools, librarians have seen first-hand the importance of digital literacy, particularly as educational settings across the globe found themselves closing their doors to keep people safe and limit the spread of COVID-19. Supporting staff, parents and students alike is a big task, but with key digital literacy competencies, school librarians can improve their schools both during and post COVID-19.

Why is digital literacy important?

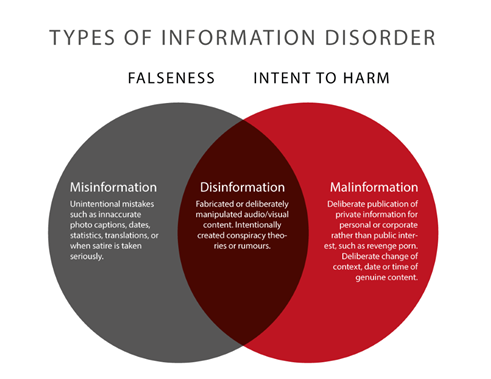

Technology has moved on at a rapid pace since its conception. There has been a surge of information – Twitter alone has roughly 500 million tweets per day (Twitter Usage Statistics, 2020) – and with that, there has also been a rising amount of false information (Mian & Khan, 2020). The insurmountable task of combating ‘fake news’ means that being able to identify credible online sources and recognising mis-information, dis-information and mal-information is an important skill for school librarians, but also for the students going through our educational systems and their parents/carers. On a more positive note, digital literacy can allow us to form supportive bonds. At a time when people can feel isolated, being able to reach out and give information that signposts towards well-being, giving online lessons, or creating fun activities to promote a sense of community in the face of adversity. These are all skills that will strengthen and benefit schools post-COVID-19 as well as during.

Digital Literacy Competencies

Schools promote education both in and out of the classroom. In order to do this, there is a requirement that staff develop their digital literacy competencies. Digital literacy is constantly evolving – as more technologies become available – but some of the competencies that should be considered include:

- Critical thinking. Being able to identify credible online sources, to recognise bias, and evaluate whether something contains misinformation, disinformation or mal-information. Passing on inaccurate content can be harmful, so it is important for school librarians to hone their investigative skills and provide accurate information.

- Communication. Finding and disseminating content at an appropriate level for your intended audience. It is important to recognise that some parents/carers will have English as an additional language, and some students will have special or additional needs. Passing on information at an appropriate level is incredibly important and it might reduce unnecessary further communication due to confusion. Likewise, teachers may want more in-depth information to supplement questions that may be raised. It is always important to remember to try and balance providing enough information with the potential for information overload. Some strategies may include:

- Use of a portal, with both public (parent/carer, student) and private/internal (staff, governors) facing ends that allow information to be shared at an appropriate level for each.

- Social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc) could allow information to be shared, and for the school to be promoted.

- Apps (ParentMail, ParentPay etc) can be used for communication, paying for trips, filling in consent forms and notifying the school of absence (freeing up the school office to take other calls).

- ‘There is strong evidence for the positive role that good quality and reliable news plays in society.’ (LSE.ac.uk, 2020, p.16). At a time when people might be feeling more isolated, digital connections can be a vital link. Sharing information, photos, quotes, and local links that support mental well-being reminds everybody that the school is there as a supportive community.

- GDPR laws are crucial, especially when schools often have personal and sensitive information regarding children. Schools also have a legal requirement to share certain documents on their school website. Please check your country’s requirements for this. For the UK, please visit: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/what-academies-free-schools-and-colleges-should-publish-online

One last piece of advice

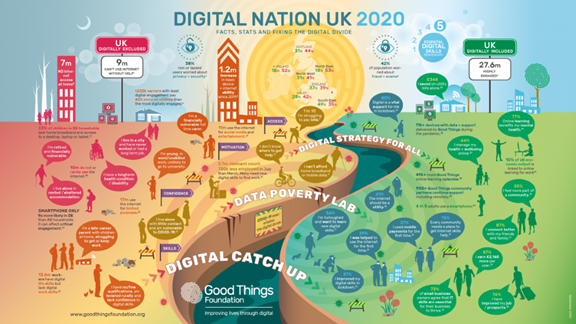

As is often the case, digital literacy isn’t quite as straightforward as we might hope. One of the main considerations for school librarians to remember is that there is still a digital gap. Some parents and children might not have access to a reliable internet connection, or even to the internet at all. A good resource can be found through The Good Things Foundation, which aims to fix the digital divide by scrutinising what limits people’s accessibility to digital technology, through looking at the facts and statistics regarding the UK’s digital divide. They provide an easy to read infographic (see below) and stress the importance of supporting individuals without internet access.

At a time when digital literacy is becoming so important, it can be easy to unintentionally widen the digital divide. Speaking to parents/carers and gauging whether they are able to access the school’s online communication can help to make sure that information is still provided to them, even if that is verbally or using hard-copies. Giving basic information about improving digital literacy can also help strengthen their knowledge and confidence online. It is our duty to support everybody within the school setting, and to work towards making sure nobody is left behind. Keep up the good work!

References

COVID19.WHO.INT., 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [online]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 28 November 2020].

GOODTHINGSFOUNDATION.ORG., 2020. Digital Nation 2020. [online] Available from: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/research-publications/digital-nation-2020 [Accessed 25 November 2020].

GOV.UK., 2020. What Academies, Free Schools And Colleges Should Publish Online. [online] Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/what-academies-free-schools-and-colleges-should-publish-online [Accessed 27 November 2020].

INTERNET LIVE STATS., 2020. Twitter Usage Statistics. [online] Available from: https://www.internetlivestats.com/twitter-statistics/#rate [Accessed 29 November 2020].

Lse.ac.uk., 2020. Tackling The Information Crisis: A Policy Framework For Media System Resilience. [online] Available from: https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/assets/documents/research/T3-Report-Tackling-the-Information-Crisis-v6.pdf [Accessed 26 November 2020].

MEDIA@LSE., 2019. DisinfoWars: A Taxonomy Of Information Warfare. [online] Available from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2019/09/27/disinfo-wars-a-taxonomy-of-information-warfare/ [Accessed 26 November 2020].

MIAN, A., KHAN, S., 2020. Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. [online]. BMC Med 18(89). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01556-3 [Accessed 29 November 2020].