New Voices RGU Student Series – Niall MacDonald

Category: New Voices, New Voices, RGU Student Series

In the Robert Gordon University Student Series blog, we share the views of RGU students from the MSc in Information and Library Studies course.

Today, we hear from Niall MacDonald, an Edinburgh-based student, on the role he thinks libraries can play in combatting fake news and misinformation.

As 2020 came to a close and COVID-19 showed no signs of disappearing, it’s fair to say that many things had become apparent during the year. From anti-mask protests to a seemingly infinite parade of opposing facts and statements in the media, you could be forgiven for thinking humanity is now more divided than ever. COVID, at the very least, has succeeded in bringing to the fore what is quickly becoming one of the most important educational dilemmas of the past 20 years: How do information professionals equip the emerging generation with skills in evaluating information for a post-COVID environment?

Given that Ofcom recently stated that the internet is the most popular platform for receiving current news among 16-to-24-year-olds (82%), (Jigsaw Research, 2018) it’s clear that the digital literacy skill of information evaluation needs to be explored. What a post-COVID world will consist of at this point is still very much uncertain, but what is certain is that there are going to be repercussions from this pandemic felt for a very long time, with the public continuing to be faced with moral dilemmas on a daily basis. Being digitally literate and able to distinguish between COVID fact and fiction could have a huge impact on the spread of this disease. If you believe COVID to be a hoax, for instance, which more than a fifth of people in England did in 2020 (Young, 2020), you are proven to be less likely to accept a vaccination, take a diagnostic test, or even wear a face mask.

As the world changes after COVID so indeed does the role of the information professional. There needs to be an emphasis within secondary schools to develop student’s information competencies so that graduates can make well-informed decisions. The evidence suggests that although there has been progress made in the last 10 years in implementing the digital skills that are crucial to digital literacy (UNESCO, 2016), there is also a wealth of evidence to suggest that high school students around the world are NOT well equipped in the information analysis strand of digital skills, such as evaluating the authenticity of a media source.

We could be forgiven for thinking that because a typical high school student is tech-savvy and extremely adept in the newest form of social media that seemingly baffles anyone above the age of 25 (TikTok anyone?!) that teenagers would be digital literate to a degree where they could decipher fact from fiction. This, however, is sadly not the case. (Perdana, R., 2016.) Stanford History Education Group, for example, found only 20% of pupils in a survey adequately questioned media authenticity and source. (Stanford Libraries, 2016) A report by Annmarie Singh highlighted similar problems while showing that pupils made consistent improvement after receiving library instruction. (ACEJMC, 2020)

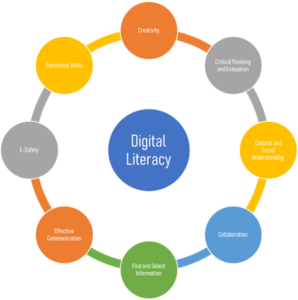

All too often, we desire the quick fix and it’s easy to overlook the practices of education in dealing with pressing issues, but COVID has proved that this simply can’t be underestimated. There are digital literacy educational frameworks in existence, with organisations such as Futurelab (Digital Literacy Across the Curriculum, 2020) and UNESCO aiming to evaluate and improve student digital literacy. Information evaluation programmes such as Newsguard are also proving popular in public libraries, but as yet there are no mandatory dedicated classes within UK education policy. School librarians and information professionals are crucial as teachers are often not specifically trained in this field and resources are already stretched. Training librarians how to deliver tutorials specific to digital literacy is therefore of the utmost importance, in addition to properly equipping school libraries. Digital Literacy is the ability to think critically and make informed judgements about any information we find and use, empowering the next generation to convey informed views and to engage fully within a democratic society. Post-COVID, we are going to need this more than ever.

References

ACEJMC, 2020. A Report on Faculty Perceptions of Students’ Information Literacy Competencies in Journalism and Mass Communication Programs: The ACEJMC Survey. ACEJMC.

Futurelab, 2020. Digital Literacy Across the Curriculum. [eBook] Futurelab. Available at: <https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/futl06/futl06.pdf> [Accessed 29 November 2020].

Payton, S. and Hague, C., n.d. Digital Literacy In Practice. [online] Futurelab. Available at: <https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/FUTL06/FUTL06casestudies.pdf> [Accessed 5 December 2020].

Perdana, R., Yani, R., Jumadi, J. and Rosana, D., 2019. Assessing Students’ Digital Literacy Skill in Senior High School Yogyakarta. JPI (Journal Pendidikan Indonesia), 8(2), p.169.

Stanford Libraries, 2016. Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning. Stanford Libraries.

UNESCO, 2016. A Global Measure of Digital and ICT Literacy Skills. Global Education Monitoring Report. Australian Council for Educational Research.

Young, S., 2020. The Guardian, [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/coronavirus- conspiracy-theories-hoax-government-misleading-man-made-survey- a9527876.html> [Accessed 29 November 2020].