#CILIPSGoGreen – Dalia García on The Carbon Literacy Project

Category: Blog, CILIPSGoGreen

From now until November when COP26 arrives in Glasgow, CILIPS will be sharing videos, links, recommended readings and more for members who want to grow their organisation’s environmental consciousness – recognising the key role that libraries can play in supporting their communities to take vital climate action.

Today, we’re hearing from Dalia García, whose MSc Information and Library Studies dissertation at Robert Gordon University focused on the Green Library Movement in Scottish HE Libraries. In the second part of this two blog series, Dalia reflects on what is necessary to speed up the progress of the Green Library Movement and shares the inspirational impact of The Carbon Literacy Project.

How do we speed up the progress of the Green Library Movement?

Building on my previous blog, I’m sharing some conclusions from my dissertation research on the Green Library Movement in Scottish Academic Libraries. Sadly, due to only five Scottish University Libraries out of 15 agreeing to participate, I never tried to publish any results, but I would be more than happy to share the full dissertation with anyone interested in conducting similar research themselves.

The main goal of my interviews was to measure university library awareness. The open questions were especially based on Jankowska, Smith and Buehler’s exploratory study (2013) and the closed questions on MacBane Mulford and Himmel’s preliminary green assessment checklist (2010 p. 57) in their book How Green is My Library?

Thanks to the collaboration of these five academic librarians, my study was able to identify a number of issues affecting the role that environmental sustainability plays in Scottish academic libraries, most of them easily transferable to any other kind of library.

- Communication: It appeared that, even though most of the institutional academic information on sustainability was readily available online, there was a lack of communication with staff. This gives the impression that sustainability measures in some organisations stay inside the office of those in charge of putting reports together and as a worst case scenario are a matter of ticking a box to keep the EAUC and the Scottish Government happy. The fact that some staff did not really know if their sustainability efforts, big or small, were having any financial impact was a proof of this. Luckily, this issue could be solved very easily with better communication, more transparency and commitment towards real and honest activism.

- Education and research: The fact that none of my respondents in 2019 mentioned having collection materials on sustainability as a way of environmental sustainability promotion and support was slightly worrying. Research and education are the pillars of any scientific environmental breakthrough, and academic libraries are the cradle and main support for it all. This is exactly why developing and growing collections on environmental sustainability should be a goal for academic libraries and any other libraries in the sector. As William Syddall (Mayo 2019) from UNSW Sydney declares, universities have the duty to ‘teach our future leaders, who are going to be advocates of sustainability and take action on sustainability’. Academic libraries are in a real position to change things and influence the content of university courses. Libraries constantly inspire students and sometimes additional resources do not require any effort: something as simple as a poster advertising the Green Gown Awards could inspire a student to undertake game-changing environmental research.

- Advocacy and activism: Passivity needs to be challenged. Campaigning to become a green library and applying for sustainability funding or awards is another way of practising advocacy and pushing the boundaries of librarianship stereotypes. Academic libraries are in a position of power and that is why University College Cork’s Green Team has the library as its headquarters. As they declare on their sustainability website, they chose this location because ‘the library (…) is at the heart of the campus, both geographically and functionally’ (UCC 2021). Their website is a good example of what any academic library could aspire to and a model of best practice.

- One for all or all for one?: When answering ‘no’ to a question about library sustainability strategy documents, some of the respondents showed unease at hiding behind the bigger organisation as justification for inaction. Almost every library, either academic, public or in any other part of the sector, has to fight these kinds of institutional constraints, but they should not stop change. If the library cannot control certain issues, there is always the possibility of working around them to find other things that librarians could be in charge of. As recognised by Sahavirta (2012), ‘often somebody else (…) is responsible for the care of the building and (…) this does not always leave much room for action. (…)’ [on the case study of a Helsinki public library] ‘It seemed that the best option was to show others the road to becoming green.’ As they could not control building policies or purchases, they decided to concentrate their efforts on advocacy and education.

- Resource sharing: My respondents’ answers suggested that sometimes there was lack of support and that change has to come from within. If institutionally provided training is not an option and academic librarians are willing to make small changes happen anyway, there are some things that can be done. For instance, the OCLC offers a guide of recommendations to start the ‘greening’ process with small steps: Greening Interlibrary Loan Practices, exploring the issue of ILL packaging and office paper use, and also recommending many helpful saving tricks (Massie 2010). Reaching out and teaming together is the best way to influence, so if in doubt, contacting another library that is ahead of the sustainability game is always a possibility.

- Training: Knowledge helps people feel empowered. Some of my interviewees recognised that their awareness of sustainability matters had increased just because of the questionnaire, which took more or less 45 minutes. This is a not so complex topic that can be understood with simple training, but institutions cannot expect staff to use their own time to train themselves, nor expect busy librarians whose roles do not mention sustainability at all to find out about awards or funding without support. Unlike complex library systems that take practise and time to master, here a simple day workshop could make all the difference. A way of solving this could be a Carbon Literacy session for staff provided by a trainer from the Carbon Literacy Project or even putting together an institutional Carbon Literacy course following the recommendations on their website (Carbon Literacy Trust 2021).

The Carbon Literacy Project

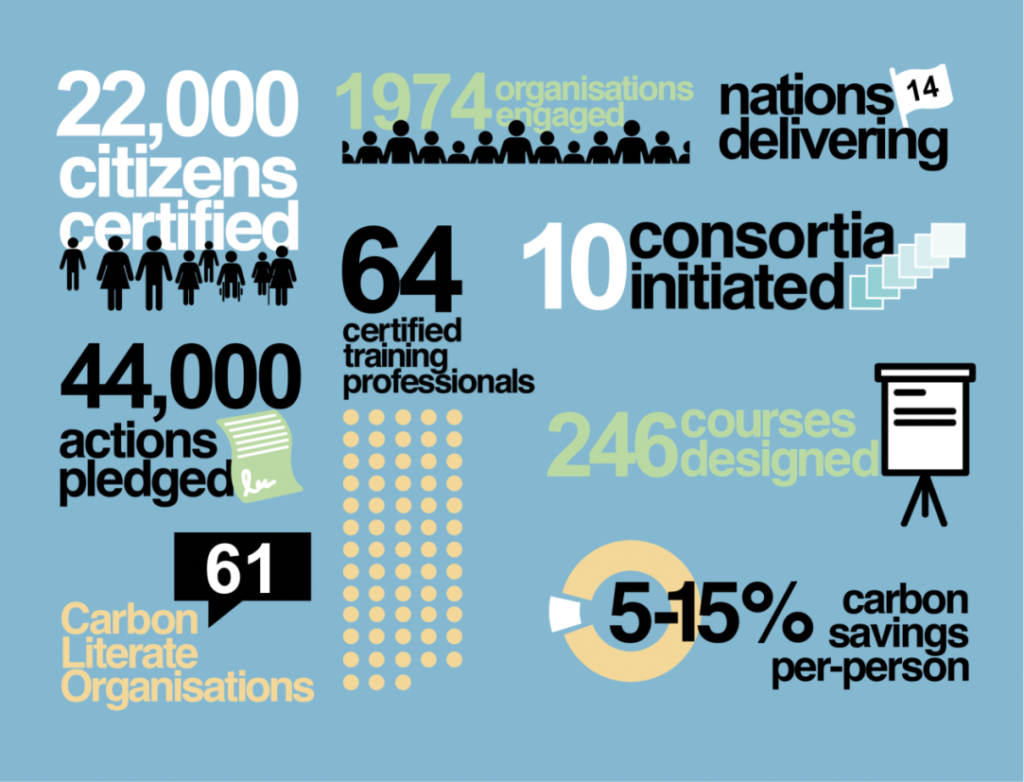

While I was researching this topic I found about the Carbon Literacy Project (CLP), a training programme that started in Manchester in 2009 with the aim of increasing awareness and helping others to reduce their carbon emissions through individual and group action. I decided I had to enrol and see for myself what that Carbon Literacy Certificate gives you in order to be able to talk about it, and I am so glad I did.

The day workshop I attended took place at the University of Edinburgh, and Keep Scotland Beautiful was delivering the session on behalf of the Carbon Literacy Project. There were between 12 and 16 attendees from varied professional backgrounds, and I was the only student at the time. The workshop was divided in four topics: the more scientific aspects behind climate change; social equity; personal action; and how to communicate action.

Far from the doom and gloom that some people would expect, the course was fun and interactive. We worked in groups, played games and during one of them I was shocked to learn that a single email has a bigger carbon footprint than a banana.

Now that I am currently working part-time in a University Library, I can see how all the things I learned with the CLP could be transferred and how much of a difference it could make if more staff members everywhere had access to this training through their organisation. I am convinced that the librarians I interviewed would have scored much higher on awareness had they received this training, and they would also be much better equipped for action.

Training aside, it is worth having a look on the CLP website for the resources and the guides alone, or signing up for the Carbon Literacy Newsletter email to keep up with news and opportunities.

Hoping that you have found some of my research notes useful, I would like to finish this blog on a positive note by quoting the same fragment I used to close my dissertation:

‘I know there are climate horrors to come, some of which will inevitably be visited on my children (…). But those horrors are not yet scripted. We are staging them by inaction, and by action can stop them. Climate change means some bleak prospects for the decades ahead, but I don’t believe the appropriate response to that challenge is withdrawal, is surrender.’ (Wallace-Wells 2019 p 31)

Please do not hesitate to get in touch!

Dalia Garcia @dalia_dahlia_

Thank you so much to Dalia for sharing such thoughtful and constructive recommendations, as well as for highlighting the excellent work being done by the Carbon Literacy Trust. To re-read Dalia’s first #CILIPSGoGreen blog, please click here.

References

CARBON LITERACY TRUST, 2021. Become a CLO. [online]. Available from: https://carbonliteracy.com/organisation/become-a-clo/ [Accessed 5 October 2021].

JANKOWSKA, M.A., SMITH, B.J. and BUEHLER, M.A., 2013. Engagement of academic libraries and information science schools in creating curriculum for sustainability: An exploratory study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 40(1), pp. 45-54.

MACBANE-MULFORD, S. and HIMMEL, N. A., 2010. How green is my library?. Santa Barbara, US: Libraries Unlimited.

MASSIE, D., 2010. Greening Interlibrary Loan Practices. [online]. OCLC Research. Available from: https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/events/2010/01-15a.pdf [Accessed 5 October 2021].

MAYO, N., 2019. THE World University Rankings: How green is my university?. [online]. Times Higher Education. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/how-green-my-university [Accessed 5 October 2021].

SAHAVIRTA, H., 2012. Showing the green way: Advocating green values and image in a Finnish public library. IFLA Journal, 38(3), pp. 239-242.

UCC, 2021. UCC Library Sustainability. [online] Cork, Ireland: UCC. Available from: https://libguides.ucc.ie/librarysustainability [Accessed 5 October 2021].

WALLACE-WELLS, D., 2019. The Uninhabitable Earth. A Story of the Future. UK: Penguin Random House.