New Voices RGU Student Series 2023 – Nicki Carter

Category: Blog, New Voices, New Voices, RGU Student Series

In this 2023 Student Series for the New Voices blog, the CILIPS Students & New Professionals Community will be sharing the views of Robert Gordon University students from the MSc in Information and Library Studies. With special thanks to Dr Konstantina Martzoukou, Teaching Excellence Fellow and Associate Professor, for organising these fantastic contributions. This series will be shared by CILIPS Graduate Trainee Leah Higgins.

Thank you to Nicki for this blog that will touch on some of the nuances and new approaches to digital literacy in Primary Education, considering the impact of Covid-19. Nicki Carter currently works at the Penguin Random House Archive and Library as a Senior Archive and Library Assistant. At present, Nicki is studying for her MSc Information and Library Studies part-time, and, in any spare time she has after that, she reads or plays with her cats.

Thank you to Nicki for this blog that will touch on some of the nuances and new approaches to digital literacy in Primary Education, considering the impact of Covid-19. Nicki Carter currently works at the Penguin Random House Archive and Library as a Senior Archive and Library Assistant. At present, Nicki is studying for her MSc Information and Library Studies part-time, and, in any spare time she has after that, she reads or plays with her cats.

1.1 Digital literacy in primary education

The impact of Covid-19

We are living in the digital age (IGI Global 2022), in a digital society, so digital literacy has never been more important. The Covid-19 pandemic increased the number of people using the internet and interacting online (European Commission 2020) and had a huge impact on education:

“[R]emote learning during the pandemic further accelerated the need to use digital resources for both learning and communication.” (Daughtery and Hansen 2022)

If digital resources are being utilised more in education, then students and teaching staff need to know how to use and interact with them effectively. However, remote learning over lockdown highlighted a digital divide, primarily affecting disadvantaged children (Coleman 2021). One factor of this is digital skills, which the school librarian can help with by teaching digital literacy – beginning at primary school.

Jisc (2014) defines digital literacy as “those capabilities which fit an individual for living, learning and working in a digital society”.

What might you be doing that employs your digital literacy skills? Maybe you use social media, online banking, watch TED Talks, shop online, email or catch up on the news.

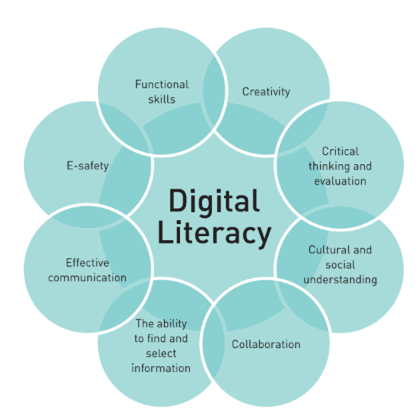

Digital literacy is more than being able to use the internet or a computer. It is about how to:

• Navigate the digital environment to find appropriate data

• Communicate and collaborate effectively

• Understand and evaluate information

• Protect your data

These are essential skills to learn in the classroom to help access, interpret and use new information. By equipping primary pupils with these skills, the school librarian enables them to “navigate their own quests for information” (Gibson and Smith 2018), in everyday life as well as education.

Teaching practices

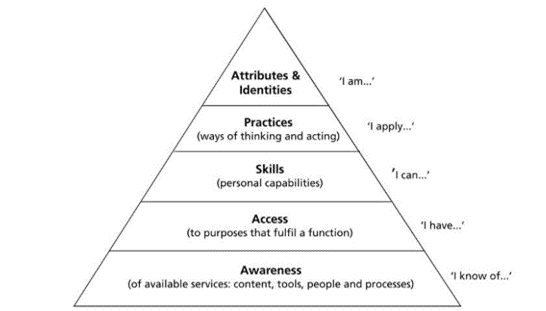

Beetham and Sharpe’s modified learning literacy development framework (Jisc 2014) shows how digital literacy skills are developed from awareness to higher level capabilities.

Focusing on the initial stages of awareness to understand their digital engagement is a great starting point for primary students:

• Are they using social media?

• Do they know what fake news is?

• Where do they look for information?

The model shows how this can be built on to develop new skills and practices based on the individual’s motivation. From here, enabling pupils to evaluate information is key. Children are especially vulnerable to misinformation online (Howard et al. 2021). Teaching pupils the difference between fact and opinion, and where they can find out the authors of information, begins to address this.

Moreover, by working with colleagues, the school librarian can make learning these skills more relevant to students’ learning and give it context. Students could find different types of sources and identify their purposes for a History topic or start a blog for English. By engaging with digital literacy in their learning, they develop skills they can develop in further education. Therefore, communication across the school departments is crucial. Checking if staff are already teaching digital literacy, and if learning resources can be shared, fosters an environment of collaboration.

Perhaps staff awareness and development in digital literacy is needed to get it embedded in the curriculum (Reedy and Parker 2018), as, if educators use and model wider digital literacy skills, it increases the pupils’ awareness. Not all primary schools have a school librarian, in which case do teaching staff need to be trained to take on this role, or should the education system incorporate this role when staffing teams?

Fundamentally, teaching digital literacy from primary education gives students a firm foundation for future engagement in higher education and life in a digital society.

Thank you to Nicki for this interesting contribution to the discussion of the impact of Covid-19 on digital literacy in Primary Education.

Stay tuned for more in the 2023 New Voices RGU Student Series coming soon and be sure to check out the rest of CILIPS SNPC’s New Voices blog.

Additional resources

Here are some helpful resources to refer to for teaching digital literacy in primary education:

https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/futl06/futl06.pdf

https://resourced.prometheanworld.com/digital-literacy-classroom-important/

https://thebig6.org/thebig6andsuper3-2

https://www.twinkl.co.uk/teaching-wiki/digital-literacy

Bibliography

CAMERON, J., 2022. Photo of boy watching through iMac. Available from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-boy-watching-through-imac-4145243/ [Accessed 28 November 2022].

COLEMAN, V., 2021. Digital divide in UK education during COVID-19 pandemic: Literature review. Cambridge Assessment Research Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Assessment.

DAUGHTERY, M. and HANSEN, L.B., 2022. Teaching Digital Literacy is a 21st Century Imperative & This is Why. [online]. Available from: https://thejournal.com/articles/2022/08/10/teaching-digital-literacy-is-a-21st-century-imperative-and-this-is-why-part-1.aspx#:~:text=In%20classrooms%2C%20digital%20literacy%20enables,in%20the%20world%20around%20them [Accessed 17 November 2022].

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2020. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2020 Thematic chapters. Brussels: European Commission.

FAUXELS, 2019. Photo of people doing handshakes. Available from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-people-doing-handshakes-3183197/ [Accessed 24 November 2022].

GIBSON, P.F. and SMITH, S., 2018. Digital literacies: preparing pupils and students for their information journey in the twenty-first century. Information and Learning Sciences, 119(12), pp. 733-742.

HAGUE, C. and PAYTON, S., 2010. Digital literacy across the curriculum. Bristol: Futurelab.

HOWARD, P.N., NEUDERT, L., PRAKASH, N. and VOSLOO, S., 2021. Digital misinformation / disinformation and children. New York: UNICEF Office of GLobal Insight and Policy.

IGI GLOBAL, 2022. What is Digital Age. [online]. Available from: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/resource-sharing/7562 [Accessed 17 November 2022].

JISC, 2014. Developing digital literacies. [online]. Available from: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-digital-literacies

REEDY, K. and PARKER, J., 2018. Digital literacy unpacked. Facet.