New Voices RGU Student Series 2022 – Victoria Le

Category: Blog, New Voices, New Voices, RGU Student Series 2022

In this 2022 Student Series for the New Voices blog, the CILIPS Students & New Professionals Community will be sharing the views of Robert Gordon University students from the MSc in Information and Library Studies. With special thanks to Dr Konstantina Martzoukou, Teaching Excellence Fellow and MSc Course Leader, for organising these fantastic contributions.

Today, we hear from Victoria Le (she/her), who currently works as a Library Assistant for the Mississauga Library at their Cooksville Branch in Ontario, Canada. Victoria is passionate about Children’s Programming and early literacy development and is dedicated to empowering young patrons. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, painting, and fly-fishing.

Today, we hear from Victoria Le (she/her), who currently works as a Library Assistant for the Mississauga Library at their Cooksville Branch in Ontario, Canada. Victoria is passionate about Children’s Programming and early literacy development and is dedicated to empowering young patrons. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, painting, and fly-fishing.

‘How can we help?’ – How Information Professionals Can Support the Digital Literacy Needs of Higher Education Students

Our world today continues to become increasingly digital without any signs of slowing down. Digital literacy skills are required and employed more often than you might realize – every time you log onto your online banking, read an email, text a friend and even when searching for and accessing this blog post. It becomes obvious how critical these digital literacy skills can be for those looking towards the future in pursuit of lifelong learning and thus why information professionals should assist Higher Education students in acquiring and refining these skills.

What does it mean to be digitally literate? According to the IFLA (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions 2017), ‘to be digitally literate means one can use technology to its fullest effect – efficiently, effectively and ethically – to meet information needs in personal, civic and professional lives.’

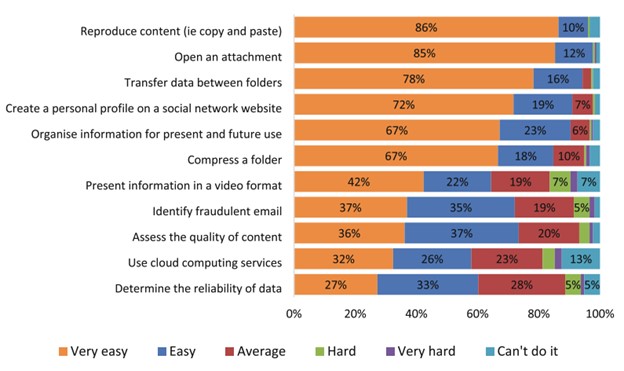

A 2018 survey of student’s self-assessed digital literacy skills conducted by Miranda, Isaias and Pifano showed that although the majority of students were confident in their abilities and expressed that the tasks were either ‘very easy or easy’, when presented with tasks at a higher level of difficulty the percentage of respondents that selected ‘can’t do, very hard or hard’ were 19% when using cloud computing services, 16% when presenting information in a video and 11% when determining the reliability of data (Figure 1). Although some students perceive their digital literacy skills to be average or above average, some may be overconfident and their ability to critically evaluate sources and websites, use digital tools and effectively apply these skills are actually less than adequate (Jeffrey et al. 2011).

Figure 1. Level of difficulty in completing specific operational tasks

(Miranda, Isaias and Pifano 2018 p. 82 fig. 5).

So, how can information professionals help?

Take for example, the diverse digital literacy needs of law students and nursing students where law students might apply their skills in ‘…delivering and managing online client services and requests, using automated processes, legal management software and digital tools (e.g. automated platforms for legal transactions and organising and managing cases, offering time tracking and scheduling of appointments and managing files) and using cloud services…’ (Martzoukou et al. 2021 p. 2) and nursing students might use their skills to access healthcare services, track patient outcomes and critically evaluate medical information to aid in their decision-making process (Theron, Borycki and Redmond 2017). Customizing the digital skills training and making it directly relevant to the students can support their learning and ‘…ameliorate student anxiety and confusion with using specific digital tools or adopting particular behaviours within the online environment’ (Martzoukou et al. 2021 p. 2).

Information professionals would need to address any challenges including limitations in their own (and their staffs’) digital literacy skills and issues with limited time allocated with the students. Academic librarians should evaluate the need for any upskilling to update and bolster staffs’ digital literacy skills and collaborate with educators in the different disciplines to customize the training offered to students ensuring that it is relevant to their field and allowing for scaffolding of learning according to different needs. The York University Libraries in Ontario, Canada offers faculty/instructor support in the form of digital and information literacy classes in all disciplines for students and outlines how to “…find, retrieve, evaluate, analyze, consume and create information…” (York University 2019)(Figure 2).

Figure 2. Screen capture from the York University Libraries’ ‘Book a Library Class’ webpage (York University 2019).

Digital literacy skills are critical for Higher Education students’ employability as they complete their programs and venture into the professional world. In this digital age, employers value graduates with the digital skills, competency and ability to critically evaluate and create using digital tools and services. With help from information professionals, Higher Education students will be in a position to benefit from opportunities to bridge any existing gaps in their digital literacy skills, gain confidence in using digital tools and become better digital citizens while pursuing lifelong learning.

Thank you to Victoria for sharing this analysis of the integral and irreplaceable role that information professionals play in supporting Higher Education students to develop information literacy skills.

Stay tuned for more in the 2022 New Voices RGU Student Series coming soon and be sure to check out the rest of CILIPS SNPC’s New Voices blog.

References

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF LIBRARY ASSOCIATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS, 2017. IFLA Statement on Digital Literacy. [online]. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Available from: https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/1283 [Accessed 25 November 2021].

JEFFREY, L. et al., 2011. Developing Digital Information Literacy in Higher Education: Obstacles and Supports. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 10, pp. 383-413.

MARTZOUKOU, K. et al., 2021. A study of university law students’ self-perceived digital competences. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. [online]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006211048004 [Accessed 25 November 2021].

MIRANDA, P., ISAIAS, P. and PIFANO, S., 2018. Digital Literacy in Higher Education: A Survey on Students’ Self-Assessment. In: Z. PANAYIOTIS, and A. IOANNOU, eds. Learning and Collaboration Technologies. Learning and Teaching. Proceedings of the LCT: International Conference on Learning and Collaboration Technologies. 15-20 July 2018. Las Vegas: Springer International Publishing. pp. 71-87.

THERON, M., BORYCKI, E. M. and REDMOND, A., 2017. Chapter 8 – Developing Digital Literacies in Undergraduate Nursing Studies: From Research to the Classroom. In: A. SHACHAK, E. M. BORYCKI and S. P. REIS, eds. Health Professionals’ Education in the Age of Clinical Information Systems, Mobile Computing and Social Networks. London: Academic Press. pp. 149-173.

YORK UNIVERSITY, 2019. Book a Library Class. [online]. Toronto: York University. Available from: https://www.library.yorku.ca/web/ask-services/facultyinstructor-support/book-a-library-class/ [Accessed 26 November 2021].