New Voices RGU Student Series 2023 – Willow Drye

Category: Blog, New Voices, New Voices, RGU Student Series

In this 2023 Student Series for the New Voices blog, the CILIPS Students & New Professionals Community will be sharing the views of Robert Gordon University students from the MSc in Information and Library Studies. With special thanks to Dr Konstantina Martzoukou, Teaching Excellence Fellow and Associate Professor, for organising these fantastic contributions. This series will be shared by CILIPS Graduate Trainee Leah Higgins.

Thank you to RGU student Willow Drye for this excellent blog contribution. After initially achieving a masters degree in Youth Literature, Willow decided to pursue a second masters degree having worked in a library for a short while. They enjoy fiction in all of its forms, as either a consumer or creator.

How media and information literacy can play a key role in newly-arrived immigrants’ integration.

Source: Pixabay.

1.1. Why information literacy isn’t enough

Information literacy (IL) is a concept with many definitions and applications, and its use in public libraries is only one of them. Its importance is especially relevant when it comes to public libraries and how they can offer services tailored to newly-arrived immigrants. It is well established that their IL tends to be lacking (Shen 2013), and public libraries can be a place where those information literacy gaps can be improved under the guidance of librarians (Oduntan and Ruthven 2020).

What is particularly noteworthy is that through the improvement of their information literacy skills, immigrants are, in turn, more apt at integrating within their new country (Eskola, Khan and Widen 2020).

However, it can be a daunting task to figure out which approaches and services are best suited for this specific group when basing oneself on IL alone. Every immigrant possesses different skill levels, literacies and needs, and answering properly to their request is more often than not challenging.

As such, it is at times necessary to break IL down into smaller, more digestible pieces. Not only would it make it easier for the immigrants to acquire each skill, but also make it easier for the librarian to identify and teach the required skill(s) more effectively.

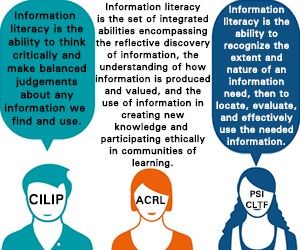

This idea isn’t novel in itself and several models exist breaking down information literacy. Whether it is an umbrella term encompassing different literacies, or a subcategory of another literacy, varies. However, in every case, it is recognized that IL cannot exist on its own, in a world that rapidly increase its complexity ever since the invention of the Internet (Godwin 2012).

“Media and information literacy covers competencies that enable people to critically and effectively engage with information, other forms of content, the institutions that facilitate information and diverse types of content, and the discerning use of digital technologies.” – Unesco

1.2. Solution: Media and information literacy

In our modern age, it is nearly impossible to obtain information without it getting filtered by media and echo chambers. As such, media literacy cannot be divorced from information literacy any longer.

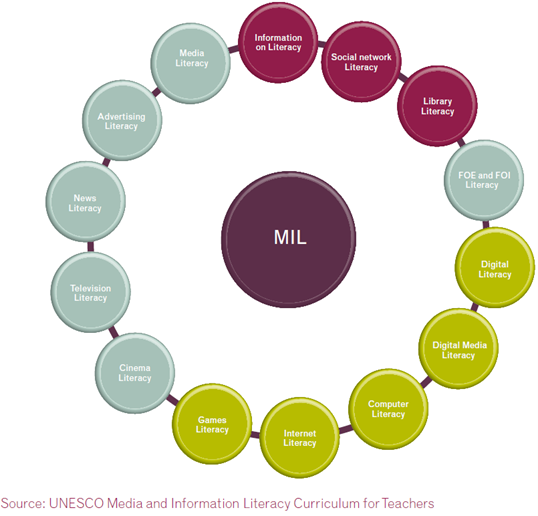

The second reason is that not only does this model consider MIL as a single group, but it represents it as an umbrella term that includes several kinds of literacy that they define as “competencies”. Rather than list each of them, I provided a graph, created by UNESCO, to help the reader have an overview of the different literacies MIL encompasses.

I consider it to be an excellent starting point for both immigrants and librarians alike. I encourage the public librarians interested in the ability to improve their services to immigrants to either create their own graphs or use the present one as a point of reference when evaluating how to best serve their customers. Whether such a graph would be reserved for the librarians as a quick evaluation tool, used to establish with the immigrant which aspect specifically they can help them with, focus on or teach them, or even freely available or accessible for the library’s customers, is up to what is most suited for each library.

1.3. Some challenges remain nonetheless

In case such graphs would be available for the public or used for the public in one way or another, one of the key challenges that a librarian can encounter is the language barrier. In those cases, it might be advised to involve immigrants by encouraging them to become mediators between the staff and the community (Grossman 2022). This would also further encourage immigrants to visit public libraries, as it would give them a sense of belonging (Muhambe 2019).

Moreover, a librarian cannot be an expert in every field and, as such, it might be recommended to establish collaboration between other fields’ practitioners or specialists and the library (Grossman 2022). In case a public library cannot afford to teach its customers some specific skills due to a lack of resources, time or teaching skills, an exceptional option would be to recommend guidebooks (Information literacy: a practitioner’s guide). It has to be noted, however, that few books tend to be beginner-friendly. A library could create its own simplified graphs or texts instead by basing itself on pre-existing guidebooks.

One last possibility is to provide or recommend tutorials, whether self-made or pre-existing. For example, some libraries have published several videos on YouTube serving as tutorials, about how their library functions or how to perform research. See the example of the YouTube channel of the school library of Southwestern Michigan College below.

Lastly, a more novel idea, that could only work for libraries with enough resources, could be to hire people with different areas of specialisations: one librarian specialised in digital and computer literacies whereas another specialises in news and media literacies. As such, the customer could more easily be redirected to the most suited librarian, and librarians wouldn’t have to be expected to master every single literacy.

More ideas and challenges could be explored. For readers who wish to further explore this topic, I would recommend reading the US Citizenship and Immigration Services’ Library Services for Immigrants: A Report on Current Practices. The report considers not only current practices, but also explores several recommendations.

Thank you to Willow for this fantastic investigation into how Media and Information Literacy can play a key role in newly-arrived immigrants’ education.

Stay tuned for more in the 2023 New Voices RGU Student Series coming soon and be sure to check out the rest of CILIPS SNPC’s New Voices blog.

1.4. Bibliography

THE ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGE & RESEARCH LIBRARIES, 2015. Framework for information literacy for higher education. [online]. Chicago: Association of College & Research Libraries. Available from:

https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/infolit/framework1.pdf [Accessed 12 November 2022]

ESKOLA, E., KHAN, K.S., and WIDEN, G., 2020. Adding the information literacy perspective to refugee integration research discourse: a scoping literature review. In: C. COLE, ed. Information seeking in context. Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference., 28-30 September 2020. Pretoria: Information Research.

Available from: http://informationr.net/ir/25-4/isic2020/isic2009.html

[Accessed 12 November 2022]

GODWIN, P. and PARKER, J. 2012. Information literacy beyond library 2.0. London: Facet.

GROSSMAN, S., et al., 2022. How Public Libraries Help Immigrants Adjust to Life in a New Country: A Review of the Literature. Health Promotion Practice, 23(5), pp. 804-816.

INFORMATION LITERACY GROUP, 2018. CILIP Definition of Information Literacy 2018. [online]. London: Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. Available from:

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip/information_professional_and_news/press_releases/2018_03_information_lit_definition/cilip_definition_doc_final_f.pdf [Accessed 12 November 2022]

MUHAMBE, B., 2019. Information Behaviour of African Immigrants: Applying the Information World Theory. Mousaion. 36(1), pp. 1-18.

ODUNTAN, O. and RUTHVEN, I., 2020. People and places: Bridging the information gaps in refugee integration. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72(1). Available from: https://asistdl.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/asi.24366 [Accessed 12 November 2022]

PLATTSBURGH STATE INFORMATION AND COMPUTER LITERACY TASK FORCE, 2001. Definition of Information of Information Literacy. [online] New York: Plattsburgh State University of New York. Available from:

http://web.archive.org/web/20031230173912/http://www.plattsburgh.edu/library/instruction/informationliteracydefinition.php [Accessed 12 November 2022]

SHEN, L., 2013. Out of Information Poverty: Library Services for Urban Marginalized Immigrants. Urban Library Journal, 19(1), pp. 4-7.

Available from: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ulj/vol19/iss1/4 [Accessed 12 November 2022]

UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION, 2022. About Media and Information Literacy. [online]. Paris: United Nations educational, scientific and cultural organization. Available from:

https://www.unesco.org/en/communication-information/media-information-literacy/about

[Accessed 12 November 2022]